In preparation for the SBTS Greek Reading Group (Click here and here for more details), I wrote a basic introduction highlighting elementary information about the Didache. Over the next two weeks, I'll be posting portions of that text.

The Didache Pt. 1: Why Read the Didache

The Didache Pt. 2: Modern Discovery and Textual Status

For more information about the Didache reading group email swilhite at sbts dot edu

* * * * *

Canonicity

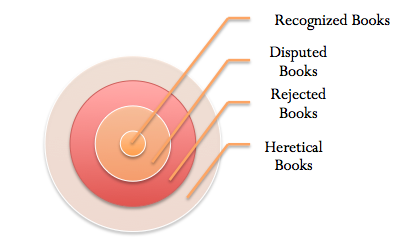

The Didache makes no internal claim to possess authoritative scripture. There are many allusions to the canonical gospels and seeks to highlight a number of their teachings. “The Didachist, while sometimes creatively re-arranging canonical material, knew that authority lay in those scriptures, and not in himself. There are no attempts to present himself as a channel of divine revelation.”[1] In Eusebius’ four-fold rubric, the Didache (τῶν ἀποστόλων αἱ λεγόμεναι Διδαχαὶ) is placed in a category called νόθος (illegitimate).[2] Eusebius has four categories into which he placed Christian literature: (1) Recognized Books (ὁμολογούμενα); (2) Disputed Books (ἀντιλεγόμενα); (3) Rejected Books (νόθος), and; (4) Heretical Books.[3] Eusebius makes a distinction between groups 2–3 and 4 so that group 3 (including the Didache) was considered orthodox, though non-canonical.

These [category 3] would all belong to the disputed books [category 2], but we have nevertheless been obliged to make a list of them, distinguishing between those writings which, according to the tradition of the Church, are true, genuine, and recognized, and those which differ from them in that they are not canonical but disputed, yet nevertheless are known to most of the writers of the Church, in order that we might know them and the writings which are put forward by heretics…To none of these [category 4] has any who belonged to the succession of the orthodox ever thought it right to refer in his writings.[4]

Eusebius, therefore, attributes orthodoxy to categories 1–3.[5] Canonical category 3, though orthodox, was not regarded as Canon but was still regarded by the Church Fathers as useful and beneficial.[6]

Figure 1: Eusebius’ Canonical Rubric[7]

[1]Varner, Way of the Didache, 53.

[2]On νόθος, consult David R. Nienhuis, Not By Paul Alone: The Formation of the Catholic Epistle Collection and the Christian Canon (Waco, TX: Baylor University Press, 2007), 65–68. Though νόθος is pejoratively used in other places in Eusebius, Nienhuis argues there is no reason to see this negatively and is a status of canonization: it is not legitimate.

Henry G. Liddell and Robert Scott, Greek-English Lexicon: With a Revised Supplement, 9th ed. (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1996), 1178; G.W.H. Lampe, ed., A Patristic Greek Lexicon (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1961), 918.

[3]Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History, 3.25.1–7.

[4]Ibid., 3.25.6–7.

[5]Nienhuis, Not By Paul Alone, 66.

[6]Michael J. Kruger, Canon Revisited: Establishing the Origins and Authority of the New Testament Books (Wheaton, IL: Crossway, 2012), 268.

Consult Varner’s work for more Patristic data asserting this claim. He also mentions Clement of Alexandria, Origen, Athanasius, and various codices. Varner, Way of the Didache, 11–14.

[7]A similar figure is found in Kruger, Canon Revisited, 268.